Author: Yilun

Translator: chatgpt 3.5, Yilun

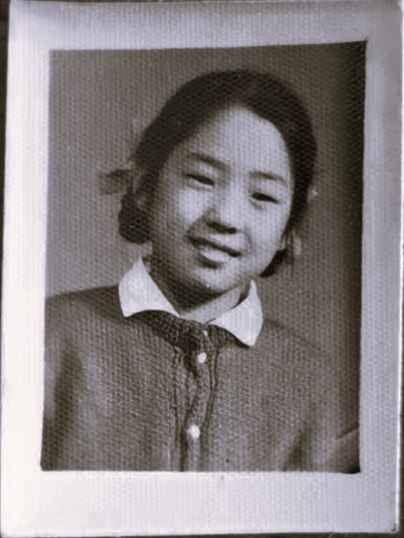

Yao Mei, born in Zibo, Shandong, China, 1963

Narrator: Yao Mei

Key terms:

Waipo=maternal grandmother

Waigong=maternal grandfather

Childhood

The stordy goes on…

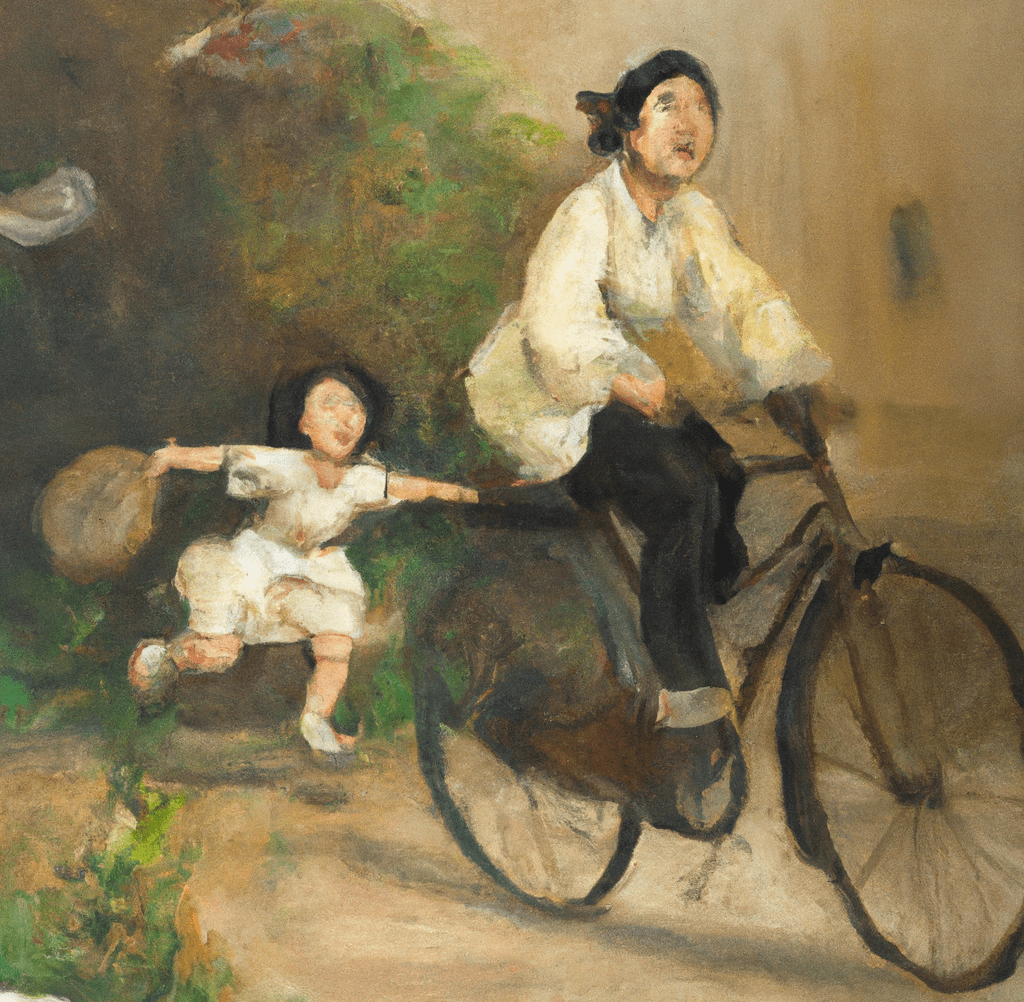

“Grandpa, where are you going?” That summer day, I hurriedly stopped him as he was about to leave.

Grandpa was fiddling with his large-wheeled bicycle. “I’m going back to Majia (Waigong’s home village),” he replied.

“I want to go too!” I insisted.

“You?” Grandpa stopped and looked at me. “How will you go?”

…

A neighbor came out with a small-wheeled bicycle passed to my grandpa and asked, “You riding this?”

Grandpa shook his head and pointed at me.

“She riding it?”

I nodded.

The large 28-inch-wheel bike was too tall for me, and I couldn’t figure out the front and rear brakes at first. As soon as I started riding, I accidentally knocked over a street sweeper. Grandpa quickly got off his bike to apologize—the people back then were kind and wouldn’t give you a hard time. The street sweeper waved his hand, indicating it was fine, but asked Grandpa in confusion, “Why are you riding two bikes alone?”

Grandpa shook his head and pointed at me.

“She riding it?”

I nodded.

…

After twenty miles, Grandpa looked back at me.

He saw me standing on the left pedal, with left leg bent and right leg extended, reached through the bike’s frame to the right, pedaling up and down. I was panting heavily, barely keeping up with Grandpa. “How much farther?” I asked.

“Thirty more miles,” he replied.

…

Passing through the Ya Wang Kou village, the villagers were astonished at the sight.

“Oh my, where did this girl ride from?”

“Lixia District, from Shanshui Gou.” Someone said.

“Fifty miles!”

“That’s right, Xiao Mei is really something!”

“Xiao Mei? The girl who saved Miaozi here?”

“Yes, that’s her.”

“Xiao Mei is really amazing!”

…

My grandparents indulged my wild nature, and I did all these things for one reason: I wanted to prove that I could take responsibility. I wanted to make them proud of me and bring them happiness. Their encouragement made those tough days joyful, providing me a wealth of spirit that material satisfaction could never compare to.

I had two aunts, Kang Rong and Wang Aihua, who attended Baotuquan Road Elementary School with me. Although they were only a year or two older than me, in the land of Confucius and Mencius, there were many proprieties, so I had to call them “Auntie.” The two of them fought every day, but I got along well with both. One day at school, I forgot to do my Chinese homework. It wasn’t a big deal, but I had a reputation for being a good student and couldn’t bear to lose face, so I lied and said I hadn’t brought it. The teacher must have seen through my lie because, since the school was close to home, she told me to go back and get it. What a disaster! In my despair, I suddenly had a brilliant idea—my Aunt Kang Rong was a grade above me, so she must have done this assignment before! I quickly sought her help. She took me home and lent me her old textbook to copy from. Although the essay was slightly different, it was close enough and saved me.

My Waigong’s younger brother passed away early, and his widow didn’t remarry but stayed in the south house of my Waigong’s siheyuan,Chinese quadrangle, with her three children (my Aunt Kang Rong was the youngest). At that time, there were also the Hou family, the Ma family, and the Hao family living in the quadrangle. Neighbors were very close back then. The street near my Waigong’s house was special, with most of the residents being former workers from my Waigong’s woodworking shop. After liberation, the shop closed, and the workers found other jobs, but these families remained as close as kin. Even though my Waigong’s family had fallen on hard times, the camaraderie from the woodworking shop, his service in the army, and the kindness of my grandparents to the neighbors created a culture of love and trust. This solid bond with the neighborhood stood still like a rock, preserved in the idle chatter, the yells of street vendors, and the ringing of bicycle bells. My Waigong, known as “Shengzi” by the neighbors, was called “Uncle Sheng” and my Waipo “Aunt Sheng.” My Waipo received a neighborhood subsidy until she passed away at 96, living a dignified life. Looking back, my grandparents were truly remarkable—kind, hardworking, honest, and humble. In the evenings, neighbors would gather in the courtyard to chat under the light of a kerosene lamp. The lamp illuminated many legendary stories, like those in “Qian Fu (Lurk),” “Da Zhai Men (The Mansion Gate),” and “Shao Shuai Chuan Qi (The Legend of the Young Marshal)”—I always thought my Waigong resembled Chang Hsueh-Liang (a notable young marshal). I loved listening to stories. The only entertainment back then was a transistor radio, playing series like “Hai Dao Nu Chao (Raging Waves on the Island)”—I can still clearly “hear” the announcer’s tone when he said, “Little White Shoes,” a character in the series—and “Yue Fei Zhuan (The Story of Yue Fei).”…

My time in Jinan was golden. I remember the large ceramic basin we used for bathing. My Waipo would mix the hot and cold water, close the door, scrub me first, then I would scrub her. After drying off, we would lie on the cool bamboo mat. In the winter, my Waipo would make clothes padded coats, all sewn by her own hands. There were children’s clothing stores near the West Gate, and my Waipo would take me to buy some little outfits. I learned to braid my hair at a very young age. My father worked in procurement for the electric power industry in Zibo and would often find opportunities to bring snacks to Jinan to see me from business trips. He would take me out to eat at restaurants—the first time I saw machine-made dumplings was one of those times. My first pair of fashionable red leather shoes was a gift from my father. When I put them on, he asked if they were too tight or if they fit well. I said they fit, but actually, they were too small and I never wore them again after that day. My father was a curious and fashionable person, having traveled extensively in his youth and had a great love for life. This trait was passed on to both my sister and me. Even then, I liked trendy things like literary works. My father and I both loved watching movies; you could say movies were my world, my life. The most memorable film for me was “Xiang Yang Yuan de Gu Shi (The Story of the Sunlit Courtyard),” starring Pu Keh.

I remember a time in Jinan, when I was in third grade, the movie “Du Jiang Zhen Cha Ji (Reconnaissance Across the River)” was released, and tickets were incredibly hard to come by. It was a particularly cold winter night, and my father was rarely in Jinan on business. Since I seldom saw my parents, this was a rare opportunity to spend time with my father, and I wanted to make the most of it. I begged him for a long time to take me to watch the movie. We stood in line for a long time, but the tickets sold out, and we were very disappointed. My father suggested we go home, but I was not willing to give up. At that time, waiting for another screening was difficult, not to mention the precious time spent with my father.

Just then, it seemed like heaven heard my plea. A middle-aged man somehow fell into the septic tank beside the theater. In winter, in a septic tank, out got the man from the septic tank, blowing in the cold wind, and the things sticking to him had frozen. What had also frozen was the mood for movie, so his family decided to return their tickets. Now, this was like throwing a piece of bread into a carp pond; everyone who hadn’t bought tickets swarmed around them, surrounding the family and making the whole theater area crowdy and rowdy. Seeing this, his brother shouted, “We’re not returning the tickets anymore!” and managed to squeeze out of the crowd, pulling the man onto a bicycle and riding away. The crowd immediately chased after them, and I was among the closest. As we chased, my father gradually fell behind and shouted to me, “Xiao Mei, jump onto their bike!” Hearing this, I aimed for the back seat of the wife’s bike and leaped onto it. We chased them for several miles, and finally, when they saw there weren’t many people left, they gave me the ticket for free. Alas, by the time I got back, the movie was almost over.

Returning to Zibo, I found that movie-watching opportunities had increased a lot. With many factories and mines in the area, film reels were often exchanged and shown simultaneously at different venues. People would spread the word about where movies were being screened. Over the years, I watched countless great films:

Gao Ying’s “Them and Their Couple,” “Da Li, Xiao Li, and Lao Li,” Mao Yongming’s “Small Small Moon Tower,” Zhong Xinghuo’s “Today’s My Day Off,” Han Fei’s “The Magician’s Adventure,” “The Three Laughter,” “Liu Sanjie,” “Visitor from the Icy Mountain,” Liang Yin’s “The Young People in Our Village” (my introduction to youthful romance), “Sweet Career,” “Black Triangle,” “Bold As Tiger,” “Secret Drawings,” “Wildfire, Spring Wind, Ancient City,” “The Sentry Under the Neon Lights,” “The Sentinel of Yangcheng,” “Li Shuangshuang,” “Happy Event,” “Flows East the River of Spring Water,” “Love on Lushan Mountain,” “Rupture,” “The Joyous Little Cold River,” and “Spring Seedlings.”

Each one of them bearing deep marks of the era. Many kids today probably never even heard of these. We shouldn’t lock history away in a small box. Understanding history is essential to see the present in perspective.

One day, a neighbor came over. After dinner, they stayed for tea, but we had no hot water. Waipo asked me to borrow some from Uncle Ma’s house. Later that night, Waipo boiled a pot of water for me to return to Uncle Ma. It was pouring rain outside, and Grandpa said it could wait until the next day, but Waipo insisted:

“Cannot. They need hot water for breakfast; it must go now.”

I had already gone to bed and was so reluctant. The heavy rain soaked my pants immediately. I trudged to Uncle Ma’s house, blurred was my vision by the water vapor. “Aunt Zhu (Uncle Ma’s wife)!” I shouted, holding the thermos in my right hand and pushing the door with my left. But, the second I stepped in, I tripped over a windboard they had placed to block the rain. The thermos shattered, and the scalding water spilled onto the ground, with me falling right into it. That night, I ended up in the hospital with large blisters covering my left hand and chest. Fortunately, it didn’t splash on my face, and it wasn’t porridge or gruel; otherwise, I would have been scarred for life. The pain was excruciating, and Waipo felt terribly guilty. But I never blamed her. I understood her. She was always considerate of others and never wanted to inconvenience anyone.

This reminds me of another rainy memory. In 1974, the school organized a farming activity in an apple orchard at the foot of Thousand Buddha Mountain. We learned to grade apples by size and blemish, placing them in corresponding baskets. The happiest moment was when the orchard farmers told us we couldn’t eat the apples on the trees but the ones on the ground. After a week of labor, as a reward, each of us was given about ten pounds of Red Star apples, the best quality. I remember there were also Jinshuai and Guoguang apples; Hongyu apples were very sour. Waipo always wrapped fruits in a square handkerchief and brought them to me at Liming Dam. But this time, she distributed the ten pounds of apples to every household, giving away more than twenty apples. In the end, I was left with only one or two. I was reluctant, but she always put others before herself. This was her shining humanity.

That day, it was also pouring rain. Some bug bit me in the field. Other children were picked up by their families, but Grandpa was at work, so I walked home alone. That night, I had a high fever, and the bitten area on my skin became ulcerated. Grandpa took me to the Provincial Hospital, where my fever reached 40 degrees. There were no beds available, so I lay in the corridor, burning with fever for two or three days. Waipo was very anxious. Grandpa ran to the post office to make a long-distance call to my parents. They rushed from Zibo overnight—my mother was a pediatrician—and took me back to Zibo for treatment. Because of this illness, my parents were worried I wouldn’t be well cared for in Jinan. Coupled with the household registration issues, I said goodbye to the big north house where Waipo, Grandpa, and I lived with the thermos.

Jinan symbolizes the love Waipo gave me, the love she gave everyone. This love, delicate yet vast, transcends time and surpasses everything.

My shoes bought by my father, the movies we watched together, the anxious waiting by the window for his arrival, were my paternal love. Waipo’s morning silhouette, the burns from the hot water, the fruits wrapped in a square scarf on the high Liming Dam, and the stargazing with her were my maternal love. Altogether, they are my childhood.

I miss those days so much.

…

“Waipo, look at that star, that one is so bright!”

“Wow, that one is really bright, just like our Xiao Mei,” Waipo said, slipping a piece of sweet melon into my mouth.

I chewed and laughed, “Waipo, look at that one, that one’s so big…”

…

At night, the stars in the sky twinkle brightly. I look at the star, my Waipo. I know she is the brightest one up there, always watching over me.

To be continued…

Pictures and content from: