Author: Yilun

Translator: Chatgpt 3.5, Yilun

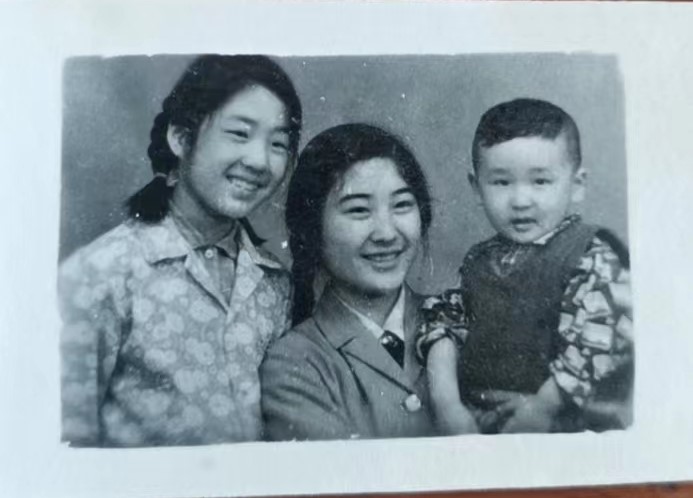

Yao Mei, born in Zibo, Shandong, China, 1963

Narrator: Yao Mei, my Mom

Key terms:

Waipo=maternal grandmother

Waigong=maternal grandfather

Childhood

“One’s lifetime is either cured by childhood, or spent curing childhood.”

Story goes on…

In the year I turned ten, 1973, my Waigong was released from prison ahead of schedule due to the easing of tensions between the Kuomintang and the Communist Party, putting an end to nearly two decades of incarceration. At that time, the impact of the Cultural Revolution on my parents was gradually fading away, and in October of the same year, they were blessed with a son, my younger brother, at an advanced age, whom they named Hongyun, meaning “the great auspiciousness”.

However, the joyous occasion for our family was struck by another bolt from the blue. My uncle had been sent to the countryside for ten years due to his family background and was unable to return home in the city. Seeing no hope of returning, my uncle decided to settle in the rural area, build a house, and get married. It seemed like a stable life was within reach, but a year after the completion of the five-room house, my uncle suffered a sudden gastric perforation while working and, despite efforts by fellow villagers to transport him to the county hospital on a makeshift stretcher made from a door, he passed away on the way.

During that time, our home in Jinan was enveloped in a gray cloud. My Waipo said it was “一命换一命 (pinyin: yi ming huan yi ming)”, a life for a life, expressing that she would rather my Waigong had not been released from prison so that our family at least could have remained intact. It was only until later, when my mother was airing the bedding, that she discovered a letter written by my Waigong, revealing the news of my uncle’s passing. I suddenly realized that my Waipo hadn’t shed a single tear during the days of her daughter’s postpartum recovery.

Due to the need for someone to care for my Waipo in the wake of my uncle’s death, I transferred from the Zibo Nanding Power Plant Affiliated School to Bao Tu Quan Road Primary School (also known as Zhengjue Temple Street Primary School) in Jinan.

The primary school was located in an old mansion resembling Guangzhi Courtyard. With the Great Chinese Famine’s aftermath, the Chinese population had surged, resulting in too many students in the same grade. As a result, we were divided into morning and afternoon classes. I developed a passion for literature and art from primary school, participating in various literary and artistic activities such as writing, singing, and dancing. At the time, our class teacher was Ms. Feng Aidong, who taught Chinese. She was tall, with a ponytail and dimples. As my outgoing and likable personality was unlocking, coupled with the talent in writing, I was deeply favored by Ms. Feng, who appointed me as the captain of the school waist drum team. We rehearsed every afternoon and frequently participated in activities. There were many political movements at the time, such as criticizing Lin Biao and Confucius, denouncing Deng Xiaoping, and the publication of the fifth volume of Mao’s Selected Works, all of which were part of my childhood.

There were also some incidents that would now be considered bullying on campus. I still remember those four girls, Cui, Liu, Diao, and Lou. One lunchtime, when I returned to the classroom as usual, they had pushed all the desks together, blocking the aisle and preventing me from returning to my seat. Then they began to push, shove, and hit me. There were many similar incidents, and the class atmosphere at the time was such that even my monitor, Xia Yan, followed suit and did not intervene, although she’d been treated me well. I couldn’t understand why they targeted me and crowded me out. Later, I thought it might be because I was too active and outspoken in class, and because I was an outsider, I was suppressed. Until one day, my Waipo came to the school to demand justice. I heard her say helplessly, “This child is not my daughter, what should I do if she gets hurt badly!” The school took no action. From then on, the image of my Waipo’s powerless and pale defense was deeply ingrained in my mind. At that moment, I suddenly realized that at that time in Jinan, I had no relatives, no friends, and no one to rely on except for my elderly grandmother. They bully you because they saw you as the weak one, and that was the only reason. I came to realize that respect and awe were related to ability, not kindness, humility, or submission at all. The weaker you showed yourself to be, the less likely you were to survive in this world. It was also from that moment on, I vowed to change, for my Waipo and for myself. I vowed to become stronger and make my family truly rely on me. Life is the best teacher. After that, I studied hard, my grades improved, and I gradually adapted to the new environment. My classmates also gradually became companions, communing to school altogether with me. I finally had friends.

After my Waigong’s release, he found employment in a provincial prison related company. From a well-off family, he’d never done household chores since childhood, and enlisted in the military at a young age. However, influenced by his family’s woodworking business and his own intelligence, he learned some carpentry skills, which became his livelihood after his release. Despite facing adversity, my Waigong remained optimistic about life, often mentioning his luck. He worked as both a carpenter and a security guard, forming many friendships along the way. When it came to his craft, my Waigong always brought home small pieces of wood after work, using them to craft items like small square stools and Mazha (a type of folding chair) in the evenings.

My Waipo took charge of sewing the fabric for the Mazha, while I focused on studying and assisting. With each passing day, my Waigong crafted more wooden tools, filling every corner of our home. Along with the growing collection of handmade treasures, our home was also filled with the lively and cozy atmosphere of our little family of three. Laughter and joy suffused, warming our hearts. After my Waigong’s release, two rooms given to my Waipo’s cousin were returned, providing a home for my grandparents. One of these rooms was the pointed-roofed north room, gray tiles and white walls, with ancient wooden beams supporting the ceiling. But what left the deepest impression on me was the antique bed my Waipo slept on. It was a rattan-woven bed with a canopy, curtains, wooden covers, and a footstool. Hooks on the canopy were for hanging mosquito nets, and the footstool made it easy for my Waipo’s bound feet (an old Chinese custom of breaking and tightly binding the feet of young girls) to climb in and out of bed. The rattan bed was smooth and slippery, causing the blankets to slip off during winter nights, so my Waipo had a Bizi (wicker rack) made to hold them in place. I had slept in this bed with my Waipo since I was young, while my Waigong, upon his return, slept on a Chundeng, spring stool (an ancient-style stool as my Waipo referred to it, though it was more likely a Luohan bed), which was long, narrow, but remarkably comfortable.

During that time, only the middle room among the three had a lamp. So, every night at bedtime, my Waipo would call out to my room, “Xiao Mei (my nickname), are you ready for bed? I’m turning off the light.” Later, my Waigong installed a lamp in my room as well, with wires winding around the beams like a spider’s web. The winters in the north were bitterly cold, and relying solely on a coal stove for warmth meant that getting out of bed each morning was the most challenging task. Although I was a professional at sleeping in, there was one thing that could easily lure me out of my cozy nest: my Waipo’s cooking.

In the late-dawned winter mornings of the north, my Waipo would wake up very early every day, hunched over, and light the kerosene stove under the dim light—she only used this stove for breakfast. A Tiaoan, long narrow table, and a square table constituted the “kitchen,” where the clinking of kitchen utensils flowed out. My Waipo would take out the meat filling she had prepared the night before, wrapped in gauze, and make either cabbage dumplings or steam buns. The aroma enveloped in warmth in shape of steam, wafted through the room beams, like a hook pulling at my nose, coaxing me out of bed. In those days of material scarcity, with no refrigerator to store food, we had to outwit the mice, using earthen pots to cover food or hanging them in baskets. I grew up competing with mice for food. Despite such challenging times, my Waipo gave me all her love. Her love was never expressed in words but in actions. Her love, without seeking anything in return, was the source of all my happiness. These everyday scenes are forever etched in my mind; she is the warmth in my heart, shielding me from the cold winter of the north.

My Waigong worked hard, often not returning home until eight or nine o’clock at night, riding his big bicycle. To improve his diet, my Waipo would often ask me to buy some soy milk and fried dough sticks, which were considered delicacies back then, rare and cherished.

There was only one vendor within a few miles, and they only sold for half an hour. If I wanted to buy, I had to queue up at five or six in the morning. I was actually quite reluctant to go. The soy milk vendor was at the bridgehead, a thirty-minute walk from home, and the winter mornings in the north were especially cold, with darkness shrouding everything. The ground was slippery, and walking alone was quite scary; even a cat darting out would make me shiver, wavering my heart.

“Our Xiao Mei is the best, the most understanding!”

Yet, my Waipo always praised and encouraged me, and this was the only reason I wore my Waigong’s coat, which reached down to my feet, and faced the entire starry sky. When I saw my grandparents’ happy faces as they enjoyed their soy milk and fried dough sticks, everything was worth it. For my Waipo, for the promises I had made, and of course, for the delicious soy milk and fried dough sticks, I shouldered the burden of life at the tender age of ten. Ten years old was more than enough.

To be continued…

Pictures and content from: